On Sunday morning, October 23, 1910, the Albany Argus dedicated half of the front page of its second section to a long piece on St. Paul’s Church. Titled “A Church at Work: Social Service at St. Paul’s,” the article described St. Paul’s in glowing terms as “a Centre of Social Service in Albany,” with detailed descriptions of fourteen parish activities.

The congregation that the newspaper describes is certainly energetic. But what is most impressive is that this description could be written of St. Paul’s in 1910. Only ten years earlier, a New York Times columnist had described St. Paul’s as “a church in Albany that is the very reverse of rich and marked by the signs of decrepitude sometimes incidental to advanced age.”[1]

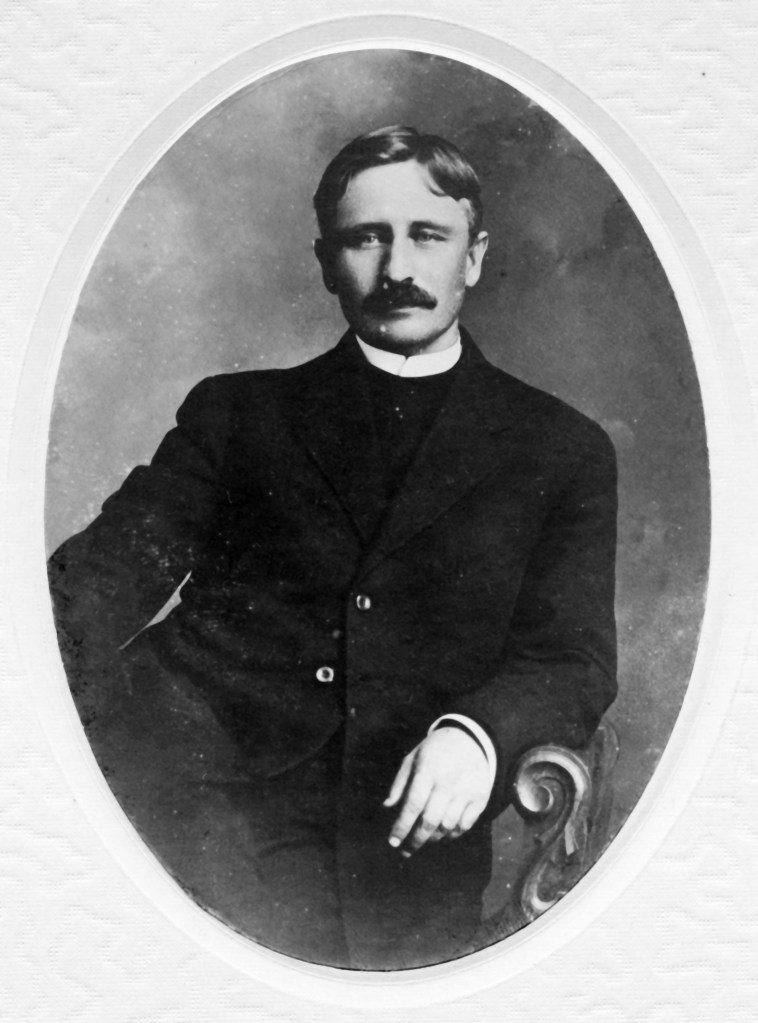

This transformation may be attributed in large part to the parish’s new rector, Roelif Hasbrouck Brooks. When he arrived in Albany in 1906, Brooks immediately began a program of rejuvenation, starting with a campaign to repair and beautify the church.

By late 1907, that effort was well under way with major enhancements to the church nave and a new enthusiasm for parish outreach.

Since then [late 1906] two windows had been put in place, two were now being constructed, a baptistery had been erected, the chancel enlarged, the organ reconstructed, two tablets had been erected and the credence table rebuilt. Meantime the Sunday-school had doubled its offerings for missions, the parish had met its apportionment and had also made various gifts for charities.[2]

The 1910 Argus article describes the motivation behind all this new activity. It seems likely that the following, connecting St. Paul’s efforts to the guilds of the medieval English church, must have been written by Brooks himself.

The church at work nowadays is an interesting development in Christianity, and one of the most active an interesting examples of it in Albany is St. Paul’s Episcopal Church.

The old and original idea of a church was a collection of people who paid a minister to preach the gospel on Sundays, and a Sunday-go-to-meeting place in which to congregate and listen to the minister’s preaching, But very far back in the history of the Church of England the development of the church at work is interestingly chronicled in a history of the English guilds, in which it is set forth in very early English that: ‘The pouere men of the parisshe of seynt Austin begunnen a gylde in helpe and amendment of here pouere parisshe churche.’[3] So it came about that the help and amendment of parish churches soon made them a meeting place on other days than Sunday, and as the guilds grew the temporal purposes of the churches broadened.

Now the calendar of the month for such a church as St. Paul’s would include a list of activities happening on nearly every day of the week to astonish an old-fashioned churchman of the once-a-week variety.

Here are the highlights from the social services listed in the 1907 Argus article:

- Mission to Deaf and Dumb, recounting the early visits by Thomas Gallaudet (dated here to 1858), and the parish’s connection with Harry Van Allen.

Services are held on the first Sunday of each month, and literary and social meetings are occasionally held. As the missionary resides 100 miles away, his visits arc necessarily short and infrequent, and it is not deemed wise to undertake to do too much, but the results of the mission work, even under such restrictions, seem to be highly satisfactory, and the mission itself is one of the most peculiar and interesting agencies tor good connected with St. Paul’s.

- St. Mark’s Chapel. The article describes the work of the Brotherhood of St. Andrew organizing a chapel in Pine Hills that grew into St. Andrew’s Church. After St. Andrew’s became an independent parish, the Brotherhood turned its attention to “the new Delaware avenue section that has grown so enormously in the last year or so.” As we have seen in an earlier post, the chapel survived only for a few years more, closing in summer 1913 when they lost the lease.

The results of attendance at the Sunday school and the afternoon service have justified the opening of the chapel. Sunday school is held on Sunday afternoon at 3:15 and a service with sermon or address at 4:30. The building, which was formerly a storehouse. has been remodeled and made comfortable, heated by a hot-air furnace and lighted by electricity. Undoubtedly as the district grows the chapel will grow until St. Mark’s will become a church by itself.

- St. Paul’s Cadet Corps. This must have been short-lived effort. I have been unable to find other references to it in Albany newspapers of the 1910s and 1920s.

St. Paul’s Cadet Corps came into existence last November and grew to a body of 50 well-drilled soldier boys under command of Major Charles B. Staats of the Tenth Regiment N. G. S. N. Y., who has drilled them Friday afternoons at 4 o’clock. The purpose of this organization is to teach the boys of the parish the life of the soldier. The boys are taught the setting-up exercises at the beginning, and later on will go to the State armory for drilling and instruction in the manual of arms. Through this corps it is hoped to produce a lot of boys who will have a soldierly bearing, who will walk erect and have a knowledge of the life a soldier in all its varied aspects.

The first meeting of the corps this season was last Friday, and there is a fine outlook for the year.

- Men’s Guild

The Men’s Guild is a sort of club for service, which has an annual banquet, an annual “moonlight excursion,” and regular meetings at which addresses were made during the year by the following: Judge Randall J. LeBoeuf, on “Alaska,” Police Justice John J. Brady, on “Juvenile Delinquents,” State Forest, Fish and Game Commissioner James H. Whipple, on ”The Preservation of Our Forests,” Prof. Jesse D. Burks on the “The Mountain People of the Philippines,” Major R. R. Biddell, “War Reminiscences.”

- Parish Aid Society. This group provided work for women in sewing aprons, towels, dusters and other small items at home. The society gave the materials, and then offered the finished product for sale to members of the church. The Society also organized a “woman’s exchange” in which women could advertise willingness to care for children or the elderly, or to make baked goods.

- Church School

The church school of St. Paul’s is 84 years old. Among the children who learned their lesson of the day at St. Paul’s were the late Bishop Satterlee and the present bishop of Los Angeles. The kindergarten was substituted for the primary department two years ago and with the full kindergarten equipment of chairs, tables and materials. The work among the children has been especially successful. The enthusiasm and loyalty of the school grows, and the “mite box” offering for mission was the largest of any school in the diocese last year.

- Altar Guild

An Altar guild sounds ecclesiastical rather than energetic, bur the Altar guild of St. Paul in the course of Iast year held five regular meetings and a number of entertainments that raised the balance due of the amount pledged toward the improvement of the chancel in commemoration of the eightieth anniversary of the founding the parish. It held a linen sale, a rummage sale and gave two plays, beside furnishing flowers for the altar and distributing them to the sick at the close of the services.

- Periodical Club

A church periodical club is a bright idea. As this little paragraph of the club urges: “The matter of sending a periodical, a paper or a magazine to some distant point to a missionary or to a mission station is a very simple and inexpensive thing. All the society asks is that your send a paper or magazine after you are through with it and pay the postage. The expense is slight. The pleasure and the delight you may give a missionary may not be measured. Why not begin with the New Year and use this simple means of making some on happy?

- Girl’s Guild. Apparently, the St. Paul’s chapter of the Girls Friendly Society (which a few decades later became one of the most dynamic of the parish’s activities) had not yet been organized.

Meetings of the Girls’ guild are held every Friday evening from September until June, and last year lessons were given for five months by Miss Hills, of the Albany Academy for Girls.

- Mothers’ Meetings

Weekly meetings of the mothers were held during last winter and four dozen garments made for the Child’s hospital, the season closing with social evening and refreshments.

- Junior Auxiliary

What does a junior auxiliary do? That of St. Paul’s church held 15 meetings last year, dressed 30 dolls for mission boxes, and gave a cake sale.

- Women’s Auxiliary

The Woman’s Auxiliary to the board of missions, St. Paul’s branch, sent boxes to North Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee, Texas, and to nearby villages in this State.

- Parish House: These activities refer to the older section of the Parish House, built in 1883. The portraits are now a part of St. Paul’s parish archives.

The demands of the future of the church will lie in the direction of an enlarged parish house where work among young people may be carried on efficiently, and this has been ensured by the purchase of vacant lots adjoining the church property. One of the interesting features of the parish house is the emphasis of the personal element in the making of a church by the collection of portraits of the men who have helped to make the church from the beginning portraits of rectors, wardens, vestrymen, uniformly framed and hung on a line about the four sides of the room, the parish family from 1827 to 1910.

- Systematic Giving: this supplemented income from pew sales and rentals. A campaign to add $100,000 to the parish endowment and to free the pews did not start for another ten years.

Systematic giving enables St. Paul’s to carry on its activities without financial handicap. Each subscriber sends to the rector a pledge card containing the amount pledged per week and the name and address of the subscriber. A package of envelopes bearing the date of the Sundays in the year is then sent to the subscriber and these are then placed upon the offertory plate, with the amount pledged inclosed.one for each Sunday, as each Sunday of the year rolls around. The amount pledged by each subscriber is a confidential matter between the subscriber and the rector.

- The article also briefly mentions that the church library has a circulation of upward of 900 books, a summer school cooking class and Christmas dinners for the poor.

The Argus article ends with a final statement of the theological motivation for these activities:

St. Paul’s ought to be a centre from which those forces which count in the Christian life should go forth and be identified with the institutions of our city which have as their aim the good and the welfare of our fellow men. We are thankful that there are men and women in St. Paul’s who count it a privilege to be of service to humanity in its largest and broadest sense. There should be no narrow parochialism nor spirit of sectarianism among us, but rather breadth of mind and Christian charity.

[1] “Topics of the Times,” New York Times 21 Jan 1900.

[2] “Tablet Unveiled in St. Paul’s, Albany N.Y.,” The Churchman, volume 96, number 16 (26 Oct 1907), page 649.

[3] Brookes may have been referring to the guild established in 1380 in the parish of St. Augustine, Norwich.