It’s Women’s History Month and I’ve been reading Susan Ingalls Lewis’s book on female proprietors in Albany between 1830 and 1885. We think of nineteenth century business as an entirely male affair. Unexceptional Women[i] shows us otherwise: many women throughout the country operated businesses in that period.

In fact, businesswomen abounded in the nineteenth-century United States. Rather than exceptional pioneers, these women were unexceptional contributors to their family economies and local communities. Neither notorious nor particularly notable, the vast majority were home-based micro-entrepreneurs who faced many of the challenges that today’s working women assume are unique to the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.[ii]

Much of the book details the experiences of women seamstresses and milliners, and of others operating small shops in Albany. But Lewis devotes a chapter to female entrepreneurs, exceptional women who took risks to expand their businesses. Once of her examples in this chapter is Julia Ridgway, whom she describes as “a woman of exceptional drive and ambition.”[iii] Julia, you won’t be surprised to learn, was a communicant of St. Paul’s Church, and matriarch of a family with a deep connection to the parish.

Julia James was born in Manchester England about 1819. She married Frederick W. Ridgway, and by the early 1840s, the couple had emigrated, and they were living in New York City. Frederick and his brother Jonathan were the “& sons” of “J. Ridgway & Sons,” a plumbing firm in lower Manhattan that seems to have begun work there in connection with supplying water from the new Croton Aqueduct. By 1843 the sons had established a plumbing shop in Albany. Jonathan soon left Albany for Boston, but Frederick continued the business here, and prospered.[iv]

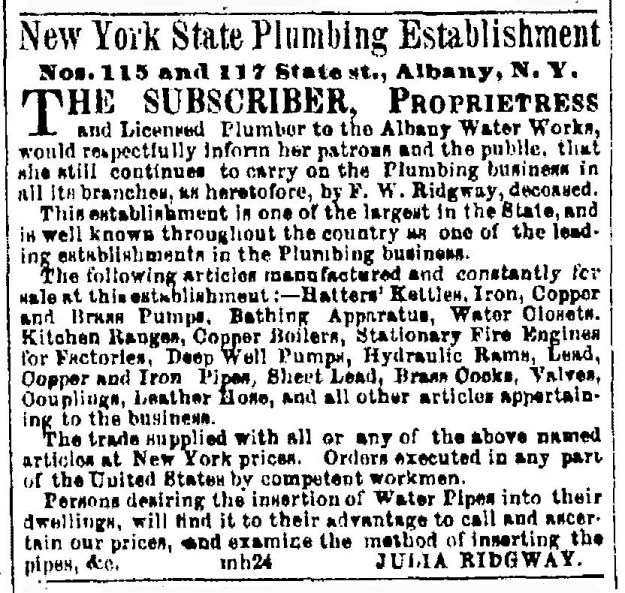

In 1851, F.W. Ridgway died suddenly at the age of 34. His young widow, the mother of two children under the age of 10, initially tried to sell the business[v]. But within a year she had decided to carry the business on by herself. In 1852 Julia advertised that as “proprietress and licensed plumber to the Albany Water Works” she would continue her late husband’s business, and boasted that the New York State Plumbing Establishment “is one of the largest in the State, and is well known throughout the country as one of the leading establishments in the Plumbing business.”[vi]

Albany Evening Journal 08 Apr 1852

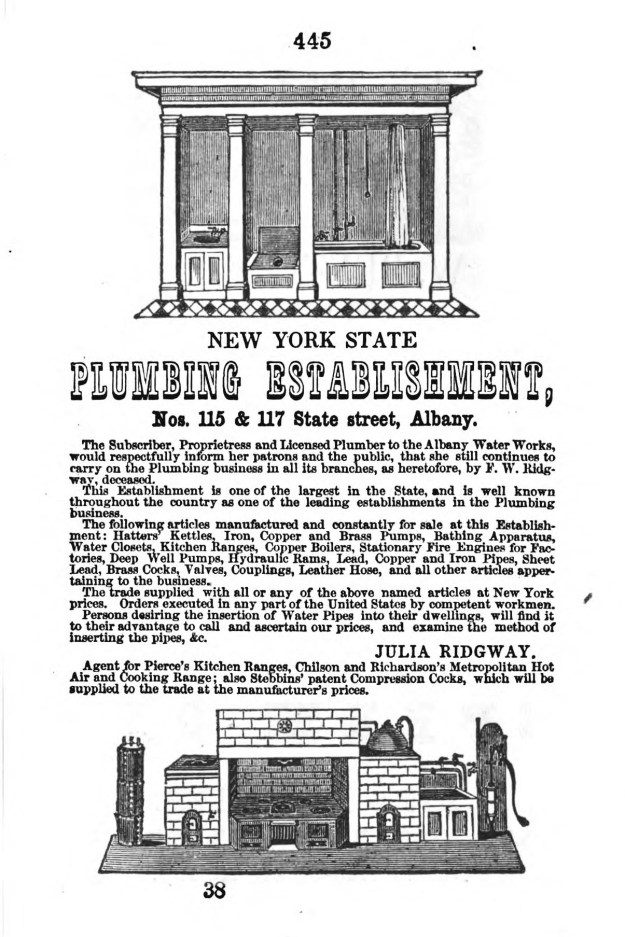

An advertisement in the 1853 city directory gives more detail on the scope of Mrs. Ridgway’s business two years after her husband’s death, promising “[o]rders executed in any part of the United States by competent workmen.” She also lists a wide variety of household and industrial equipment for sale. An illustration of a household water closet, with toilet, sink and bath, is prominently displayed.[vii]

Munsell’s Albany Directory And City Registry for 1853, page 445

Julia Ridgway did not merely keep the business going. She expanded and innovated, so that by 1865 the business was valued at triple the figure at her husband’s death a dozen years earlier. A Dun Mercantile Agency credit examiner in 1865 reported that Ridgway was “doing the best bus[iness] of any firm or man in the line in Albany,” and, he added, “clearly making money.”[viii]

I’ve been unable to find a photograph of Mrs. Ridgway. As you picture her, please don’t think of Josephine the Plumber in those 1970s Comet Cleanser advertisements. I doubt that Julia Ridgway ever donned a pair of coveralls and climbed under a sink. She was the business brains of the operation, providing capital, doing the accounting, and managing the business, but leaving the plumbing to her employees.[ix]

Part of Julia Ridgway’s success may have been due her relationships with her partners. For the first years, she relied on her husband’s foreman, Herman Henry Russ, who was also a St. Paul’s communicant.[x] As the business grew, she took on Russ and Edmond Nesbitt as partners, organizing as Ridgway & Co. When Nesbitt left the firm in 1871[xi], she reorganized the business again, as Ridgway & Russ. The business continued under that name until 1898, when her son Frederick W. Ridgway (who had been managing the firm since 1871) and Russ formed separate firms.[xii]

Grace Church, Albany (credit: Albany Group Archive)

Like Elizabeth Maria Starr Hawley (about whom I wrote several years ago), Julia Ridgway was the head of a family that included several generations of active parishioners at St. Paul’s. Julia and her daughter Mary Elizabeth became communicants in 1868, transferring from Grace Church[xiii]. Mary Elizabeth married Charles Carmichael Gould at St. Paul’s in 1876.

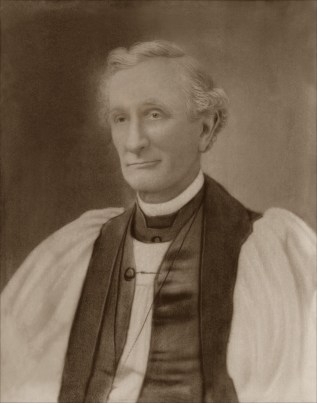

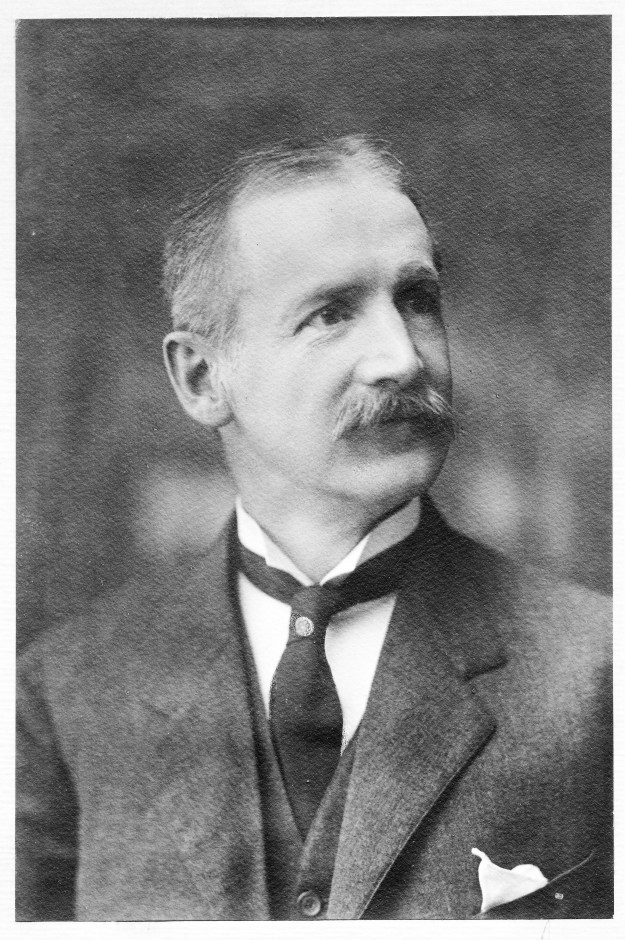

Frederick W. Ridgway

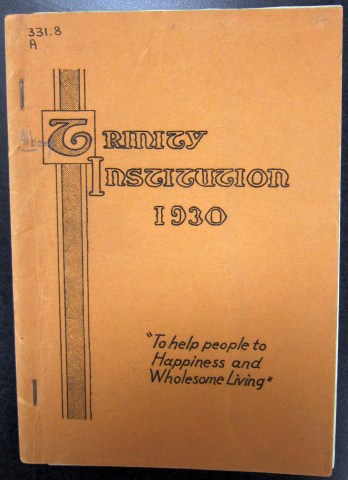

Julia’s son Frederick W. Ridgway (1849 – 1915) was confirmed at St. Paul’s in 1867. He was a parishioner for the rest of his life and a vestryman from 1901 until his death. Three of this second F.W. Ridgway’s children were closely associated with the parish. Dorothy White Ridgway (1891 – 1979) married our organist, T. Frederick H. Candlyn and was an active member until the couple left Albany in 1943. And I’ve already written about his elder daughter Elsa Ridgway (1884 – 1956), the long-time director of girls’ activities at the Trinity Institution, and about his son Frederick W. Ridgway Jr. (1896 — 1916), an active volunteer with our Sunday School.

[i] Susan Ingalls Lewis, Unexceptional Women: Female Proprietors in Mid-Nineteenth Century Albany, New York, 1830—1885 (Columbus: The Ohio State University Press, 2009).

[ii] Lewis, 2.

[iii] Lewis, 131.

[iv] Amasa J. Parker (ed.), Landmarks of Albany County New York (Syracuse: D. Mason & Co, 1897), 142.

[v] “To Plumbers,” Albany Evening Journal, 31 May 1851, 3.

[vi] “New York State Plumbing Establishment,” Albany Evening Journal 30 Mar 1852, 3.

[vii] Munsell’s Albany Directory and City Registry for 1853 – 1854 (Albany: J. Munsell, 1853), 445.

[viii] Lewis, 131-133.

[ix] Lewis, 133.

[x] “Herman Henry Russ,” The Plumber’s Trade Journal Steam and Hot Water Fitters Review, volume 43 (Feb 1908), 160. Russ’s wife Catherine was confirmed at St. Paul’s in 1863, and their daughter was baptized here the same year. Herman and Catherine became communicants in 1875 and 1880, respectively. Their children were confirmed here, and Herman’s funeral was held at St. Paul’s in 1908.

[xi] “Dissolution,” Albany Evening Journal 25 May 1871, 3.

[xii] Parker, 142. See also The Metal Worker, volume 1, number 9 (17 Sep 1898), 52.

[xiii] Grace Church had been founded in 1846, with financial support from St. Paul’s. In 1865, the church (then located at the corner of Washington Avenue and Lark Street) was unable to support itself financially, and St. Paul’s provided our assistant minister, Edwin B. Russell, to serve as their rector. That relationship lasted until 1866.

![Governor's Mansion 1925 [Photo credit: Albany... the way it was Archive]](https://grainoncescattered.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/governors-mansion-1920s.jpg?w=669&h=542)