William Ingraham Kip (portrait attributed to Asa Weston Twitchell)

In earlier posts, we have described how in 1847 St. Paul’s rector, William Ingraham Kip, proposed building two mission chapels, and how those plans failed. Our senior warden, William H. DeWitt, then offered to fund the construction of a chapel of ease for St. Paul’s, to be known as the Chapel of the Holy Innocents, and located in Albany’s North End. As the building was being constructed, DeWitt changed course, resigned as St. Paul’s senior warden and formed Holy Innocents as a separate parish. When it came time to consecrate the new building, Kip (along with the rectors of Albany’s Grace Church and Trinity Church) formally protested the consecration, and the ceremony proceeded only when certain changes were made to the church deed and Kip withdrew his protest.

A letter, held in the archives of the Diocese of Maryland, has now added substantially to our understanding of the grounds of the protest, the resolution of the dispute, and the matter’s aftermath. Kip wrote it on August 6, 1851 and addressed it to Bishop William Rollinson Whittingham, who had ruled on the protest and conducted the consecration. Kip explains his protest and the reasons that he withdrew it. More important, he describes the ill will that was continuing between him and DeWitt a year after Holy Innocent’s consecration. And he asks the bishop, whom he in later years would refer to as an “old friend,”[i] a very large favor.

William Henry DeWitt

In the letter, Kip reminds Bishop Whittingham of the two points of his protest concerning DeWitt’s deed of conveyance, in which he perpetually leased the building and grounds to the church corporation. These points were DeWitt’s assertion of:

- a right of unlimited nomination of the church’s rector “enabling him to force a Rector on them [the people of Holy Innocents]”

- the descent of the right of nomination to William and Ann DeWitt’s heirs forever

Kip then describes the resolution to the protest, in which DeWitt’s deed of gift was substantially changed by:

- restricting DeWitt’s right of nomination, by providing that DeWitt could only nominate the same person three times[ii]

- eliminating the descent of the right of nomination, so that it would end with the DeWitts’ deaths[iii]

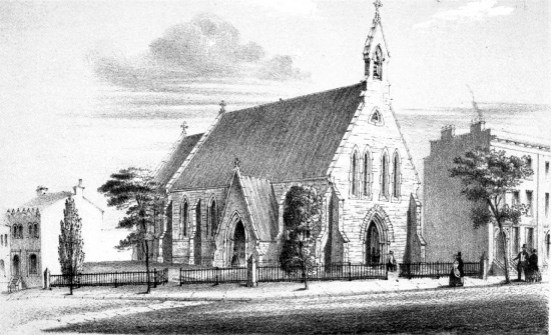

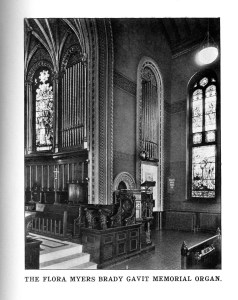

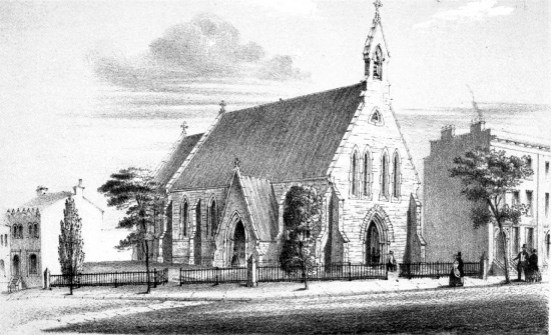

Holy Innocents

Given the long history of Kip and DeWitt’s relationship, we could guess that that this was a very personal dispute. They had worked together at St. Paul’s from 1837 until 1850. These were difficult years for St. Paul’s, and Kip and DeWitt as rector and senior warden, respectively, for that entire period worked together closely. It was through their collaboration that the parish recovered from bankruptcy and achieved financial stability. During the early, lean years, DeWitt was also St. Paul’s major financial contributor.

For his part, Kip was disappointed by the loss of the chapel and angry at provisions he saw as contrary to church law. He had proposed a mission chapel, as an outreach for a growing and thriving St. Paul’s and as an important work in furthering the mission of the church in the city of Albany. But Kip’s concern for proper ecclesiastical polity was also a factor. Shortly after the new church’s consecration, Kip’s vestry wrote him their “approbation of your proceedings in the matter of the consecration of the ‘Church of the Holy Innocents.’” In words that echoed Kip’s intentions in raising the protest:

All depend upon our clergy in keeping a watchful eye over the Church, allowing no innovations, nor dangerous precedents, rigidly adhering to its laws and in exactly observing its old landmarks. In all these things we feel we can say that you have done your duty and that you enjoy our highest regard and confidence.[iv]

DeWitt, for his part, was frustrated in his expectation of control over a chapel for which he had paid every expense, and promised to support forever. DeWitt must have felt that, having paid for the cost of both real estate and the building itself, he had the right to make it his own family church, after the model of Troy’s Church of the Holy Cross, which had been fully funded by Mary Warren and her family in 1844.

Wm. Ingraham Kip at St. Paul’s altar (from an 1847 portrait by William Tolman Carlton)

We have suspected, then, for some time that there must have been hard feelings, but did not learn until we saw this letter how the dispute had played out in the months and years after Holy Innocent’s consecration. We do not know DeWitt’s side, but Kip’s letter to Whittingham describes his view of this personal aspect of the dispute.

Kip describes how, over the year since the consecration, DeWitt has conducted a campaign of “unmeasured abuse” and “outrageous and long-continued slander.” Specifiically, Kip has heard of DeWitt “denouncing me to one of my vestry, as ‘an infamous, black, scoundrel’, (the proof being, my making that protest) & warning one of the families in my parish against me, as one whom they w[oul]d one day find out to be ‘a devil.” Kip also tells Whittingham that DeWitt has claimed that Whittingham had disapproved of Kip’s protest and that DeWitt “publicly denies that he was forced to yield anything , or that the deed has been in any way changed.” [v]

Kip’s purpose in writing was to ask Whittingham to confirm that DeWitt was wrong on all of these counts, by writing a letter affirming that the bishop had supported the protest and continued with the consecration only after two substantial changes to the deed. Kip asks that Whittingham put these in writing “in a letter of a single page” that he could show to those who believe DeWitt’s claims.

Finally, Kip asks Whittingham for his advice: would it be proper for Kip to present this matter to DeWitt’s rector, Sylvanus Reed, “demanding that he [DeWitt] be debarred from communion until he shall make proper reparation.” Kip does not mention the fact, but Whittingham may well have known that Kip was Sylvanus Reed’s mentor. Reed was the son of a St. Paul’s vestryman, had been brought up at St. Paul’s, and had been supported for ordination by Kip and St. Paul’s vestry. Whittingham would have known that a demand from Kip would certainly have been obeyed by the young Mr. Reed.

The Rev. Sylvanus Reed

Bishop Whittingham’s outgoing correspondence, sadly, has not survived. We will never know whether Kip asked Sylvanus Reed to withhold communion from William H. DeWitt. Nor do we know if Whittingham wrote the letter that Kip asked of him, and (if he did) how it might have affected Kip and DeWitt’s relationship.

If that outcome is unclear, it is more certain that failure of the mission chapel and DeWitt’s campaign of slander had an effect on William Ingraham Kip. Although he continued as rector of St. Paul’s for two additional years, his acceptance of election as missionary bishop of California may have been encouraged by the simmering conflict over the chapel of ease that never was.

In 1852, a year after this letter was written, Kip was thinking of moving on. That year, a friend suggested that Kip should express an interest in serving as rector of Trinity Church, San Francisco. Kip reported later:

The suggestion struck me favorably. I had been fifteen years in Albany, — had built up a large congregation, — and it seemed as if there was no room for progress or enlargement in the future. On the other hand, in San Francisco was a new field, — a rising empire, — and there was a freshness and enterprise in founding the Church in that region which rather fascinated my imagination.[vi]

And the controversy may have affected Whittingham view of Kip’s situation as well. As we have discussed before, he was the diocesan bishop of Maryland, acting here while the Diocese of New York had no bishop. Shortly after the discussion about the position in San Francisco, Kip was offered the rectorship in St. Peter’s Church, Baltimore, in Whittingham’s home diocese. Kip told his old friend Whittingham that he would not accept that call, but that he was tempted by the possibility of the position in San Francisco. Whittingham told him, “You must go to California, but not as a Presbyter! You must go out in another capacity.”[vii] It was the next year (1853), with backing from Whittingham and others, that Kip was elected missionary bishop of California, and left St. Paul’s Church.

[i] Wm. Ingraham Kip, The Early Days of My Episcopate (New York: Thomas Whittaker, 1892), 2, 7.

[ii] Another account describes the resolution differently: that DeWitt’s right of nomination would be “limited to three nominations and required to be exercised within a year from the occurrence of a vacancy.” [Joel Munsell, Annals of Albany, First Series, Volume X (Albany: Munsell & Rowland, 1859), 434]

[iii] The Albany Annals account describes this resolution differently as well: that the right to nominate would continue, but to William and Ann DeWitt’s issue, not their heirs. Since Mr. and Mrs. DeWitt then had no living issue, and were unlikely to have any more children (William was 51, and Ann 45), this would have had the same effect. [Joel Munsell, Annals of Albany. First Series, Volume X (Albany: Munsell & Rowland, 1859), 434]

[iv] Letter dated 20 Jul 1850 from the wardens and vestry of St. Paul’s Church to William Ingraham Kip. Held in St. Paul’s church archives.

[v] This may be what is referred to in a lengthy footnote to the Albany Annals account:

The ground of the opposition was, the nature of the reservations to the donors, and their heirs, and it was alleged that the deed of conveyance had been altered from the form in which it had been drawn up by Mr. J. C. Spencer, and assented to, as satisfactory, on the first opening of the church. The allegation was unfounded. The deed was made out in the office of J. V. L. Pruyn, Esq., and is a verbatim copy of the original draft made by Mr. J. C. Spencer, and admitted by him to contain nothing which could prevent the consecration. The Bishop received the protest; but on a conference with the donors, the right of nomination to the rectorship was limited (as by the release above), when he determined on proceeding.

[Joel Munsell, Annals of Albany, First Series, Volume X (Albany: Munsell & Rowland, 1859), 434-435]

[vi] Kip, Early Days, 1-2.

[vii] Kip, Early Days, 2.