William Ingraham Kip’s year-long medical leave (1844-1845) worked well for him and for the people of St. Paul’s: he returned in good health, and spent another eight years as our rector. Today’s post is the story of his successor’s medical leave, which ended badly and precipitated a crisis that almost destroyed the congregation.

When Kip resigned in December 1853, the vestry named as his successor Thomas Alfred Starkey, then the rector of Christ Church, in Troy, New York. Starkey arrived in February 1854. Fourteen months later, in April 1855, Starkey submitted his resignation because of ill health. He withdrew it “at the urgent request of the congregation.”[i] Then again, three years later, in April 1858, Starkey submitted his resignation because of ill health. This time, the vestry offered him a six-month leave of absence. Starkey accepted, and traveled to Europe.

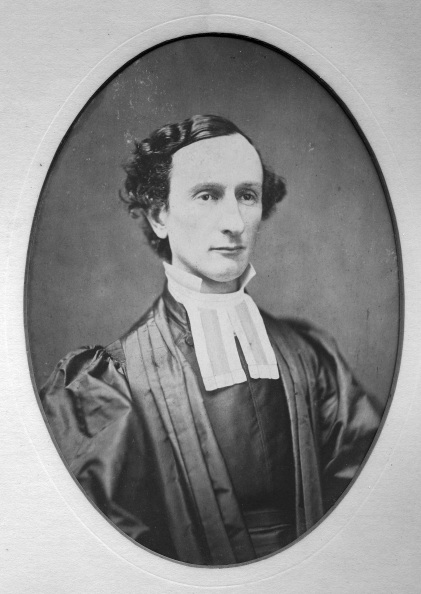

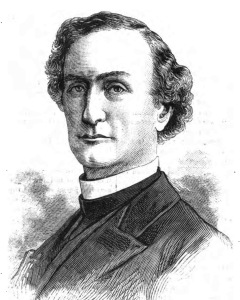

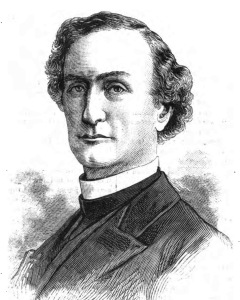

Thomas A. Starkey

Previous histories end the narrative neatly, if not happily: Starkey returns from his leave in early October 1858, announces that his health is still fragile and again submits his resignation. The vestry reluctantly accepts the resignation, and a few months later announces the call of the new rector, William Rudder. This is the account given in a 1877 sketch of the congregation’s history[ii], and followed by all historical essays since that time. The vestry minutes support this version, containing only their offer of a leave of absence, followed by his resignation in November.

But this neat version is incomplete, and hides the story of a significant dispute within the congregation that tells us much about the church and the times. To understand it, we need to return to the long, successful tenure of William Ingraham Kip. In his farewell sermon at St. Paul’s, preached December 11, 1853, he said:

We have Brethern (sic) been at peace among ourselves. There has been no party strife within our borders, even among the exciting times which for some years marked our church; but Pastor and People have been in one mind in all that concerns the welfare and progress of the Church. It is to this that we owe our prosperity and Oh remember Brethern (sic) that so it must always be, if you would not decline and relapse into feebleness.

The “exciting times” to which he refers was the period of the 1830s and 1840s, when the English Oxford Movement’s “Tracts for the Times” were distributed in the United States. As the Episcopal Church sought to balance its theology in light of renewed interest in Catholic theology and liturgy, Kip wrote a series of lectures which he presented at St. Paul’s on Sunday evenings in the winter of 1843 and later published as The Double Witness of the Church. The lectures, relying on both scripture and tradition, distinguished the American Episcopal Church from the protestant denominations on one side and the Roman Catholic Church on the other. As Kip wrote in the Preface:

[The author] believes that this work will be found to differ somewhat in its plan, from most of those on the claims of our Church, which are intended for popular reading. They are generally written with reference merely to the Protestant denominations around us. The public mind, however, has lately taken a new direction, and the doctrines of the Church of Rome have again become a subject of discussion. The writer has therefore endeavored to draw the line between these two extremes – showing that the Church bears her DOUBLE WITNESS against them both – and points out a middle path as the one of truth and safety.[iii]

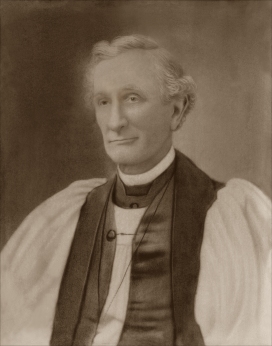

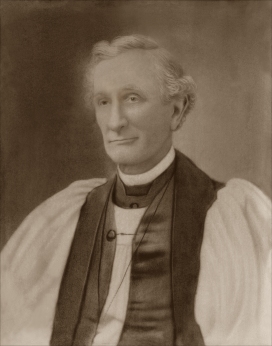

John Henry Hobart, Bishop of New York 1816-1830

The Tractarians had little influence on Kip, who saw their works as supporting the high church theology to which he already subscribed. The Double Witness, while occasioned by the Tractarian controversy, restates the position of Kip’s mentor, Bishop John Henry Hobart, who summarized his theology when he wrote “My banner is, EVANGELICAL TRUTH, APOSTOLIC ORDER.”[iv]

Thomas A. Starkey

Thomas A. Starkey was also a high churchman, but one of a very different sort. While the press described him as moderate high churchman, that term had acquired a new meaning, one much affected by the distinctive theological, devotional and social views of the Oxford Movement. Starkey described the movement glowingly in his 1877 sermon at St. Paul’s:

The period of my rectorship of this parish which extended from February 1854, to the autumn of 1858, was embraced within a very interesting and exciting portion of our general Church History. The long-continued stagnation in English and American Church life had been disturbed twenty years before by what is known as the “Oxford tracts movement.” In the old diocese the controversies, growing out of local causes had terminated two years before in the election of Bishop Wainwright, whose bright but brief Episcopate cheered the hearts of Churchmen, only to deepen the disappointment at its premature close. In the autumn of 1854, the same year in which I became rector of St. Paul’s, Dr. Potter, of St. Peter’s church in this city, was consecrated for the vacant seat; and I believe that I only reflect the general judgment when I say, that rarely has a difficult choice been justified by a wiser administration. It was a day of controversy, and at times, of strong and even angry feeling; but it was also a day of generous self-devotion and of brave endeavor for the church’s sake. The old stagnation had been completely broken and a new life stirred throughout all her borders.[v]

The fuller story of Starkey’s resignation is omitted from all church sources, but it was considered newsworthy by the popular press, allowing us to piece it together from newspaper accounts. The first article comes from the Albany Morning Express of October 26, 1858.

In St. Paul’s Church Sunday morning [24 Oct 1858], immediately after the reading of the Ante-Communion service, the Rev. Mr. Starkey came before the chancel and addressed his congregation. He remarked that six months ago the Vestry kindly gave him leave of absence for a period of time to enable him to regain his health. He left his congregation harmonious in feeling and united in action. After an absence of six months, and a return to his labors, he found a great charge in his temporal charge – his congregation distracted, and a want of harmony existing in the Parish. In view of his state of health and the condition of his congregation, he felt it his duty to resign his charge, and as Pastor he bade them farewell. His remarks and his determination were evidently unexpected to a large majority of his congregation, and were received with manifest surprise and emotion.[vi]

Thomas A. Starkey

This news was so exciting that it was picked up by the New York City newspapers. The next day’s New York Evening Post gives a dramatic account of the previous Sunday’s events with the headline “Church Excitement in Albany: Dr. Starkie Declines to Preach,” quoting reports from the Albany Daily Knickerbocker of the previous day:

During Mr. Starkie’s absence his high-church notions have been so canvassed as to lead to some considerable feeling in the church, and he resolved to sever his connection with the church. This took place in a sudden manner on Sunday morning. “Without a moment’s notice to anybody, he walked into the church and informed the congregation that he could no longer act as their pastor. Having done this he retired and left the congregation to go home without a sermon. The reasons for resigning Mr. Starkie promises to lay before the senior warden –Mr. Tweddle—when the senior warden returns from Europe, which will be in a day or two.”[vii]

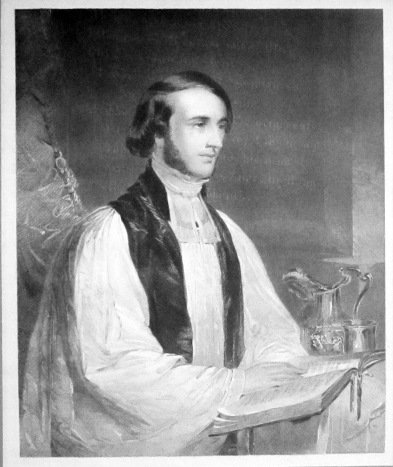

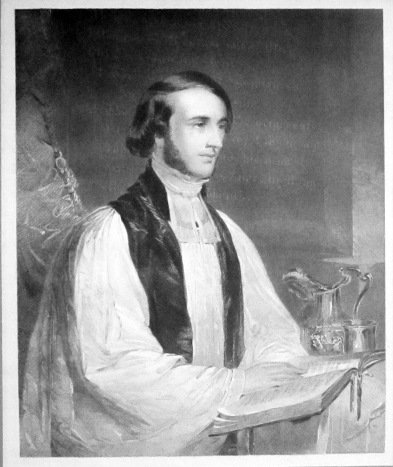

We may never know which “high church notions” were so vigorously debated (the now-archaic sense of canvassed.) The first option is that they refer to elaborate ritual practice, such as sung services, incense, sanctus bells and chasubles. In this period, however, the high church party was only beginning to be influenced by ritualism. Even twenty years later, when ritualism had spread widely, it was written that Starkey “is inclined to High Church views, but is not a ritualist in the broad sense of that term.”[viii] Starkey may however have been following ritual practices that would not surprise us at all, but that were then highly controversial. Many of these related to treating the communion table as an altar: by placing a cloth or flowers on it, or by using candles during daylight services. Another practice much debated was that of the celebrant turning to the communion table while reading the communion service, with his back to the congregation. The Book of Common Prayer directed that the minister stand at the liturgical north end of the altar (to the left, from the congregation’s point of view) during the service, as Kip is shown doing in the 1847 portrait by William Tolman Carlton.

Wm. Ingraham Kip at St. Paul’s altar (from an 1847 portrait by William Tolman Carlton)

A second possibility is that these notions were theological, and related to one of the most contentious disputes of the time: the relative weight to be given to justification by faith as contrasted with baptismal regeneration.

And a third possibility is the notions had to do with social outreach. The only activity during his rectorship that Starkey described in in his 1877 sermon was a social ministry, the establishment of St. Paul’s Church Home, a home for “homeless and aged women” [ix]. Social ministry was an interest of the high church faction in both England the United States, but not of the old-style Hobartian high churchman. Starkey tells us that the Home did not survive his departure, suggesting that the ministry was not supported by the congregation.

While the vestry minutes of November 1, 1858 record the vestry’s acceptance of Starkey’s formal resignation, they do not describe the issues that led to his resignation. What is clear is that Starkey’s resignation, did not end the dissension in the church. The Albany Daily Knickerbocker continues, accurately predicting the further problems to come:

The resignation of Mr. Starkie will, of course, increase the bad feeling existing at St. Paul’s. The result will be a grand division and a new church. Who will succeed Mr. Starkie at St. Paul’s remains to be seen. Some vote in favor of the Rev. Mr. Rudder. The friend of Mr. Starkie will be opposed to this – some of them looking upon Mr. Rudder as a sort of intruder, invited to Albany to make mischief. How the matter will finish up will be known when the senior warden arrives.[x]

William Rudder had been engaged as an interim in June to preach until August 1, 1858; in August, that contract was extended until December 1. During this period, Rudder was assisted by Starkey’s curate, Frederick P. Winne.

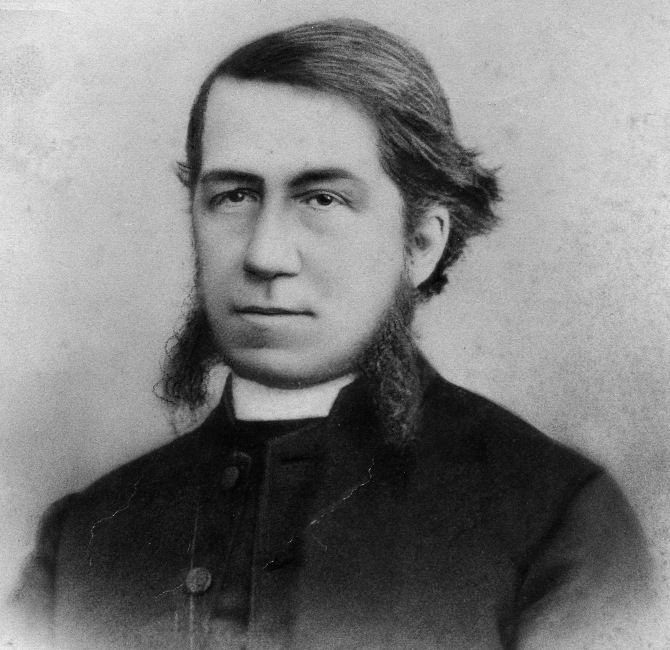

Frederick P. Winne

Rudder is vague about how he came to be called as interim from St. John’s Church, Quincy, Illinois, where he had been rector from 1857 until 1858. In his 1877 sermon he says that in 1858 he found himself in Albany as a result of “an accident on a western railroad,”[xi] was invited to preach at a friend’s church (presumably St. Peter’s, whose rector was Thomas Clapp Pitkin) where a member of St. Paul’s search committee heard his sermon, and invited him to fill St. Paul’s pulpit until Starkey returned.[xii]

William Rudder

The Rudder faction made their feelings known publicly. An undated newspaper clipping reports the gift on November 10, 1858 of a portable communion set service by “some of the congregation, who had listened with pleasure and profit to his impressive discourse.” A letter from the fourteen men is quoted, as is Rudder’s response. The fourteen include only one vestryman, Edward E. Kendrick, the cashier of the Bank of Albany. Interestingly, they also include four employees of the Bank of Albany, two of them Kendrick’s sons.

By late December 1858, chaos reigned, as the Albany Morning Express reported:

For several months past the Vestry of St. Paul’s Church has been engaged in a most unpleasant controversy, and as a matter of course, the members of the congregation have become implicated in the difficulty, there being two factions or divisions in the Church, directly antagonistic to each other. Since the commencement of the troubles, we have purposely refrained from alluding to them, nor do we intend now to recapitulate them at length. The questions in dispute between the two parties having become matters of public interest, we have therefore concluded to refer thereto. The origin of the division we do not know with certainty, Of its existence there can be no doubt, in fact it is not disputed. The resignation of the Rev. Mr. Starkey, and the reason therefor, is not unknown to the public. From that time, the difficulties increased, one faction being very desirous of calling the Rev. Mr. Rudder, and the other as much opposed to it. The cause of this opposition we do not intend to discuss. It is sufficient to know it exists. Frequent meetings of the Vestry were held at some of which the belligerent manifestations were made by and between the members. If we are not misinformed – and our authority is undoubted – language was frequently used and epithets indulged in that were far from creditable to those having the temporal management of a Church of God. So bitter were, and arethe feelings between the parties, that charges of direct falsehood have been made, without the least hesitation, and complaints preferred that de do not feel at liberty to allude to. On Monday evening meeting of the Vestry was held to choose a Rector, and a motion to select the Rev. Mr. Rudder was negatived, four of the members being in favor of it and six opposed to it. So the Church remains without a head, and the warfare continues. The result will undoubtedly lead to the secession of one of the two factions from the Church, and perhaps may even result in its dissolution entirely. – Such a state of affairs is certainly to be regretted, and very discreditable.[xiii]

This impasse was resolved during April 1859. That month, there was a major turnover in St. Paul’s vestry, with only one warden and three vestrymen reelected. Among the three continuing vestrymen was Edward E. Kendrick (a member of the Rudder faction that gave the communion service), who was elected junior warden. It is likely that Kendrick and the other three who were returned were the four who had voted for Rudder in December. The congregation also elected six brand-new vestrymen. On April 30, 1859, William Rudder was called as rector; he accepted the call in May, and became rector on June 1, 1859.

Edward E. Kendrick

St. Paul’s had somehow been able to find a way through this crisis, with no sign of a major defection by the Starkey faction. Provided with a supportive vestry, Rudder was able to serve as rector until 1863. While Starkey’s Church Home for Women did not continue, Rudder did initiate a successful ministry to the deaf, and shepherded the congregation through the financial crisis of 1862 and the decision to move to Lancaster Street.

[i] “Our City Churches – IV. St. Paul’s (Episcopal) – J. Livingston Reese, Pastor,” Albany Evening Journal, January 28, 1871.

[ii] “Historical Sketch of St. Paul’s Parish: From a Sermon by the Rector,” pages 9-17 of The Semi-centennial Service of St. Paul’s Church (Albany: The Argus Press, 1877), 14.

[iii] William Ingraham Kip, The Double Witness of the Church (New York: D. Appleton, 1844), x.

[iv] John Henry Hobart, An Apology for Apostolic Order and Its Advocates (New York: T. and J. Swords, 1807), 272

[v] “Sermon of the Reverend Thomas A. Starkey, D.D.” pages 55-63 of The Semi-centennial Service of St. Paul’s Church (Albany: The Argus Press, 1877), 56-57

[vi] “Resignation of the Rev. Thomas A. Starkey,” Albany Morning Express, October 26, 1858.

[vii] “Church Excitement in Albany: Dr. Starkie Declines to Preach,” New York Evening Post, October 27, 1858.

[viii] “Rev. Thomas A. Starkey,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, November 22, 1879, 204.

[ix] “Sermon of the Reverend Thomas A. Starkey, D.D.,” 61.

[x] “Church Excitement in Albany: Dr. Starkie Declines to Preach”

[xi] “The Sermon of the Reverend William Prall,” pages 32-42 of The Semi-centennial Service of St. Paul’s Church. (Albany: The Argus Press, 1877), 33.

[xii] “The Sermon of the Reverend William Prall,” 33-34.

[xiii] “St. Paul’s Church,” Albany Morning Express, December 29, 1858.

![Father Parke supervises painting [Times Union 9 Jul 1960]](https://grainoncescattered.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/lancaster-street-painting-nelson-parke-v001.jpg?w=300&h=248)