Rambles in local history frequently lead to surprises: we go looking for some piece of information, and stumble across something far more interesting. Serendipity struck again last month, when, purely by chance, I learned about an Episcopal orphanage for African-American children in Albany County. And the story was not new to just me: there were no references in either the diocesan history or the history of All Saints Cathedral.

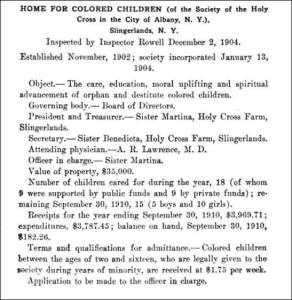

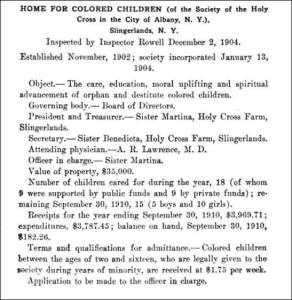

Annual Report of the New York State Board of Charities, 1910

The orphanage’s legal name was The Home for Colored Children, but it was more commonly referred to as Holy Cross Farm. It was located just outside the then city limits on New Scotland Avenue, in the hamlet of Hurstville.

The one full listing we have (from the 1910 Federal census for the town of Bethlehem) shows fifteen African-American children between the ages of two and seventeen. We know from a contemporary newspaper account[1] that it accepted children from across the State of New York. That year, there was a staff of six: a Mother Superior and her assistant, a teacher, cook, and a handyman.

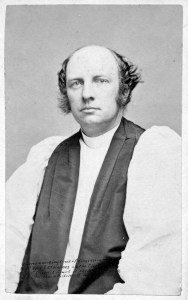

According to a city directory of the period, the Mother Superior, Stella Runyon Martin, was called Sister Martina. Sister Martina was a member of the Sisterhood of the Holy Child Jesus, an order of Episcopal nuns organized by Bishop William Croswell Doane and Mother Helen Dunham in 1873. Sister Martina’s assistant, Winifred Clare Benedict, was known as Sister Benedicta, and likely belonged to the same order.

Mother Helen Dunham, Mother Superior of the Sisterhood of the Holy Child Jesus

William Croswell Doane, Bishop of Albany

The orphanage was opened in 1902 and closed in 1914. For all but its first two years, Holy Cross Farm was directed by the Society of the Holy Cross in the City of Albany.

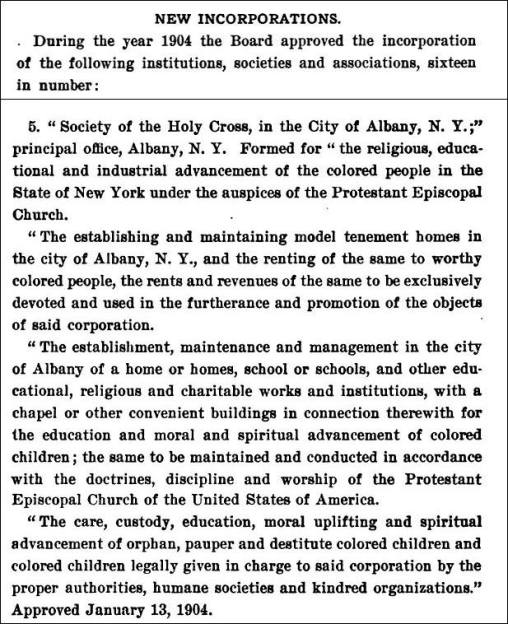

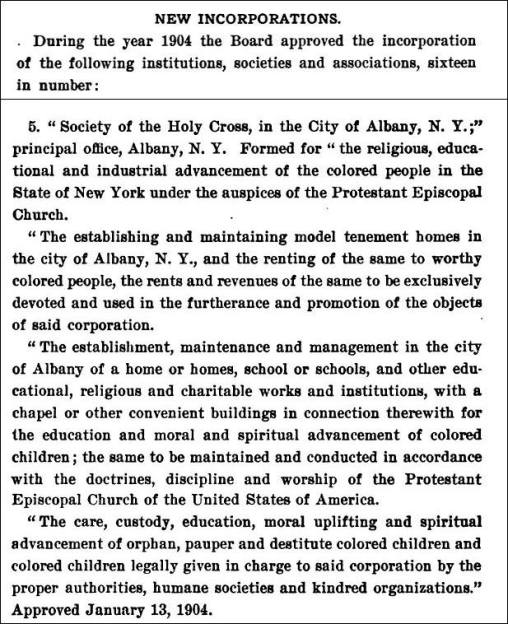

Annual Report of the New York State Board of Charities, 1904

The Society of the Holy Cross was incorporated in 1904. Its officers consisted entirely of Cathedral staff and members: the president was the cathedral’s long-time Canon Precentor, Thomas B. Fulcher, the treasurer a long-time member of the Cathedral congregation, and the secretary was the assistant Cathedral organist. The Society was formed for “the religious educational and industrial advancement of the colored people in the State of New York under the auspices of the Protestant Episcopal Church.” Three activities were planned:

- Rental housing in the city of Albany

- Homes, schools or other institutions in the city of Albany

- Care and custody of orphaned and neglected children

The first of these projects was already under way. According to the history of All Saints Cathedral[2], Sister Martina had inherited houses in Sheridan Hollow and, as a landlord, found a need among African-Americans for suitable rental housing.

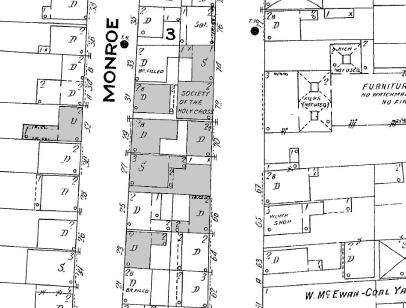

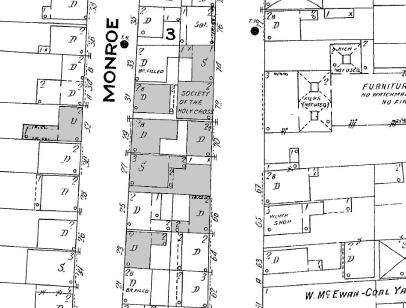

Society of the Holy Cross housing (Sanborn map, 1908)

The deeds for the properties tell a slightly different story. Sister Martina bought the houses from four different owners in October and November 1903 and assumed two mortgages; she sold the property to the Society of the Holy Cross in March 1904 and they assumed the mortgages. In 1910, the Society mortgaged the houses a second time to provide income for Holy Cross Farm[3]. Sister Martina also encouraged her tenants to join the Cathedral congregation[4]. Among these were two sisters, Georgine and Harriette Lewis.

Georgine Sheldon Lewis (University Archives, University at Albany, SUNY)

In a 1910 newspaper article[5], Georgine Lewis is described as a director of the Society, whose offices were located with the rental properties at 27 Monroe Street. Georgine was then a student at the New York State Teachers’ College in Albany; she graduated in 1911 with a B.S., and later earned a master’s degree at the same institution. She was a long-time faculty member of the Washington D.C. Teachers’ College[6]. According to the University at Albany web site, “She was the first African-American to earn a graduate degree from the University and is believed to be the University’s first African-American graduate to become a college faculty member.”[7] Georgine’s younger sister, was no less impressive. Harriette Lewis graduated from the Teachers’ Training School at Albany in 1911[8], and was the first African-American to teach in the Albany Public Schools[9]. Both sisters were members of the Cathedral congregation; Georgine was married there by Canon Fulcher, the president of the Society of the Holy Cross[10].

The Society sold the houses on Orange and Monroe Streets in January 1914 to businessman William J. Stoneman. The houses were demolished in 1924 to build a warehouse which still stands on the site.

The Society’s second project seems never to have been begun. I have been unable to find any reference to any institution other than Holy Cross Farm.

The third project refers to Holy Cross Farm and the work done there. The fact that the houses were mortgaged a second time in 1910 may indicate financial pressure on the small institution. It closed in 1914 for reasons we may never know.

Richard Henry Nelson as bishop coadjutor of Albany

We do know that Bishop Richard Henry Nelson (who succeeded Bishop Doane in 1913) did some pruning of diocesan missions early in his term. It is possible that Holy Cross Farm was one of these. The Farm continues to be mentioned in classified advertisement for a few years, but only as a farm, offering pasturage for horses. The property was sold in three separate lots between 1914 and 1916.

While the orphanage was no more, Sister Martina continued her good works. According to her obituary, she ran a home known as Mission of the Cross on Staten Island for a dozen years, and also worked in Florida. She died at the Convent of St. Anne in Kingston in 1946.[11]

[1] “Local Officials Are Pleased With Holy Cross Home,” The Binghamton Press, 23 March 1912.

[2] George E. DeMille, Pioneer Cathedral: A Brief History of the Cathedral of All Saints, Albany. (Albany: no publisher, 1967), 159.

[3] “Mortgages Its Property: Society of the Holy Cross to Improve Farm for Colored Children,”Albany Evening Journal, 8 Aug 1910.

[4] DeMille, 159.

[5] “Mortgages Its Property: Society of the Holy Cross to Improve Farm for Colored Children,”Albany Evening Journal, 8 Aug 1910

[6] “Mrs. Wilkins Dies; College Teacher,” Albany Times Union, 1 Feb 1970.

[7] “African-Americans at the University at Albany and its Predecessor Institutions – 1858-present” http://www.albany.edu/news/uablackhistory.php retrieved 5 Mar 2016.

[8] Marian I. Hughes, Refusing Ignorance: The Struggle to Educate Black Children in Albany, New York, 1816-1873. (Albany: Mount Ida Press, 1998), 80-81.

[9] “The African Voice in Albany, New York: Harriette Bowie Lewis Van Vranken Remembers” in A.J. Williams-Myers (ed.) On the Morning Tide: African Americans, History and Methodology in the Historical Ebb and Flow of Hudson River Society. (Trenton: Africa World Press, 2003), 119-139.

[10] “Wilkins-Lewis,” Albany Times Union, 24 Aug 1914.

[11] “Sister Martina, 89, Dies in Kingston,” Albany Times Union, 16 Jan 1946.

The comparison to the window design to that of Coventry Cathedral is one that is often still made. What has been forgotten over the years is the building committee’s survey of new church in New York and New England. It would be interesting to know where they visited. We know of one for certain, because an April 2, 1966 Times Union article specifically mentions it.

The comparison to the window design to that of Coventry Cathedral is one that is often still made. What has been forgotten over the years is the building committee’s survey of new church in New York and New England. It would be interesting to know where they visited. We know of one for certain, because an April 2, 1966 Times Union article specifically mentions it.

![Governor's Mansion 1925 [Photo credit: Albany... the way it was Archive]](https://grainoncescattered.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/governors-mansion-1920s.jpg?w=669&h=542)